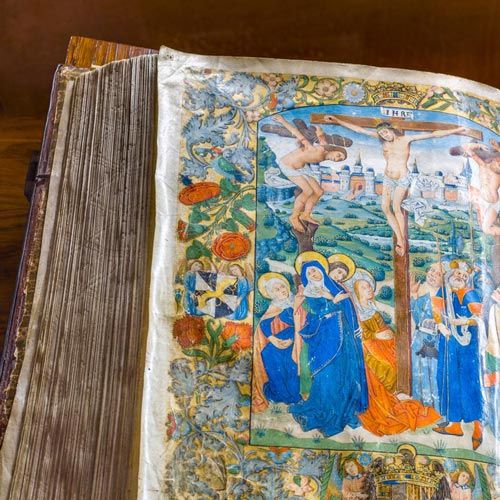

Another jewel of the Royal Chapel of Granada is the Missal painted for the Queen by Francisco Flores in 1496: «A hand-held parchment missal adorned with crimson brocade and silver adornments.» It’s made with «beautiful orles with royal coats of arms and emblems, letters with figures of saints and stories (two of them with portraits of the Queen) and a miniature of the Crucifixion on an extra page.»

The Queen’s legacy to the Chapel included an important library that in 1591 was taken to Simancas (near Valladolid) and to the monastery of El Escorial by order of Philip II. The Missal is the only remnant that stayed in the Chapel. The Inventories of 1591 and 1534-1540 are related to the books lent by the queen to the Royal Chapel: 129 according to the first Inventory and 148 according to the second.

The following text is a testimony of the Queen’s personal cultural interests, and her institutional support of the dawning Humanism of the Renaissance:

« She –Isabella I of Castile- clears the way for the humanists who communicate continually between Italy and Spain; she promotes the spreading of the printing press whose introduction in her reigns started when she came to the throne, giving tax exemption and a duty-free status to printers; she orders manuscripts copied; she supports a musician and singers school, and following in the steps of her father (King Juan II) she gathers the richest library of her time, where one can find , together with the large nucleus of religious works, many Latin classics, books of chivalry, guides to public and private behaviour to teach good government, legal and historic works, musical and dancing works, and wonderful selections of the Castilian writers of the XIV century and of all the poets of the XV century, creators of that poetry in which a new spirit appeared, a new musical sense and a sensitivity that turned what was popular into something erudite and courtly, with the same taste and refinement as a renewed breeze caressed the Gothic stones of the XV century and obtained such fine grace with which the defeated medieval art surrenders to the praise of spring and of a new spirit. »

Antonio Gallego y Burín